Some companies make better investments than others. One of the main signals to look for is the margins they operate on. Compare for example, a software company with a hairdressers. WARNING, there will be maths ahead.

If you've managed to build a good quality software service that people will pay for, maybe that cost of development is $1m. You also have some engineers you are paying $250k in salaries. And let's say for each customer you add you can charge $10 per month, and your hosting costs go up by 50 cents. I will ignore costs like marketing to make things easier.

If you have 1 customer, then you had to essentially pay $1m per customer to launch the product, then your annual costs will be just over $250k and your revenue $120. Not great.

If you have a million customers, then your development costs don't change. You spend $1 per customer to build the software, you are paying 25 cents a year to keep the development team happy, and $6 per year on hosting costs. But your revenue is still $120 per customer, so you have better and better margins as your customers grow.

The cost of adding an additional customer is low, so your profits improve much better as you grow. This is what is known to investors as "unit economics". In other words, how much money do you make on each individual unit you produce and sell.

Compare that to a hairdressers. They can say, cut 1 person per hour, they charge $40 for a haircut, but you have to pay $30 an hour for the hairdressers wages. You can fit 4 hairdressers in a salon, and the rent and bills for the salon are fixed.

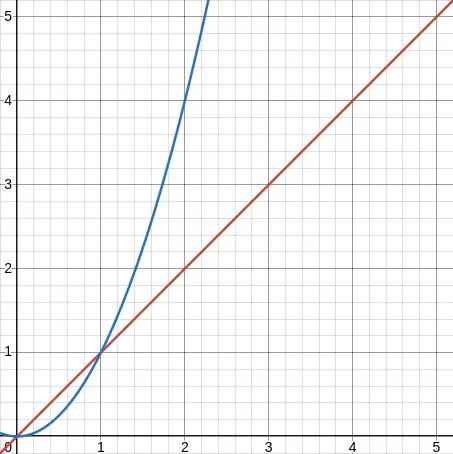

So basically, each salon produces a fixed amount of profit. Sure, you can expand by adding additional salons, but each one is going to produce the same amount. There is no acceleration that you get on a business like software. It's just a straight line.

But it's actually worse than that, because once you have 5 salons, you will need an area manager to do things like HR and recruitment. Then at some point you'll need an accountant, then your legal expenses will climb. Then you will need to do company training to maintain standards across your salon empire and so forth. So that straight line actually starts to level off after a while - you have diminishing returns.

Will it scale?

The ultimate question that investors want answered. By "scale" they mean, will you encounter diminishing returns as your sales volumes go up, or will you get accelerating returns as your sales volumes go up.

What, in effect, are your unit economics?

AI unit economics

At the time of writing, AI is the buzzword that is on everyone's mind. As our society tries to figure out the best way to utilise this new technology, some very interesting changes are happening in the unit economics of AI.

See that software example I gave earlier is why large companies like Google and Microsoft are valued so highly. There is this idea of an "initial" capital expenditure, and initial investment where you have to sink a lot of costs to build the product, learn about your customers and so on. This is called "product-market fit". Once that phase is done, most of the risk has been taken, and you enter into a growth phase. Now it's just about scaling your marketing and operations to cope with the higher volume of customers. This is the dream point for most tech start-ups as the unit economics start to work in your favour, and if they are very good, you might even get valued as a "unicorn" and list on the stock exchange for a billion dollars US.

Incrementally adding features to a product that is already well used and liked, is much cheaper (and produces much more revenue) than starting from scratch and trying to figure out who your customers are and what they are willing to pay for.

But AI is different. As far as I can tell, the unit economics kind of suck. And this is because the value is not so much in the software produced, but in the computational resource that is used to run the model.

My concept of generative AI right now, is that it is like a highly efficient search engine. You are kind of condensing the entire internet (and all human knowledge) into the model, in such a way that prompting it basically filters all that information down into the most relevant parts of the training data.

Sure it can do a bit more than that, because what you prompt with can also be data, so it can do nice data transformations (like re-writing a piece of text in a different style), and also code generation is a little different as well, but we can still really think of it as a very, very efficient search engine with a few extra benefits.

And sure, there is a high initial cost to train the model, in a similar way to building a software project. But the models require immense amounts of power and expensive graphics cards to run. They are actually really inefficient in terms of compute resource.

So unlike adding an extra user to the database, even a single user running additional queries adds a lot of cost to the AI company.

Ongoing capex

Another good source of poor margins are products that require constant capital expenditure.

Compare companies like Coca Cola vs Ford motors.

Coca Cola is selling basically the same drink they sold a hundred years ago, with the same formula, with bottling facilities that they can probably get away with replacing only every decade or two.

Compare that to a car company which can't even sell the same car two years in a row. Every year is a redesign with expensive engineers, new rounds of safety testing, regulatory burden. It's a highly competitive industry, and just to stand still requires constant expenditure. They are, expensive companies to run.

That's money which is not going back to you as an investor, it is being spent on salaries - someone else is making that money.